About Shekhawati

North of Jaipur lies the easternmost extent of the Thar Desert, where small sand-blown towns nestle between dunes and sprawling expanses of parched land. Before the rise of Bombay and Calcutta (and the arrival of railways) diverted the trans-Thar trade south and eastwards, this region, known as Shekhawati, lay on an important caravan route connecting Delhi and Sind now in Pakistan) with the Gujarati coast. Having grown rich on trade and taxes from the through traffic, the merchant Marwari and landowning thakur castes of its small market towns spent their fortunes competing with each other to build grand,

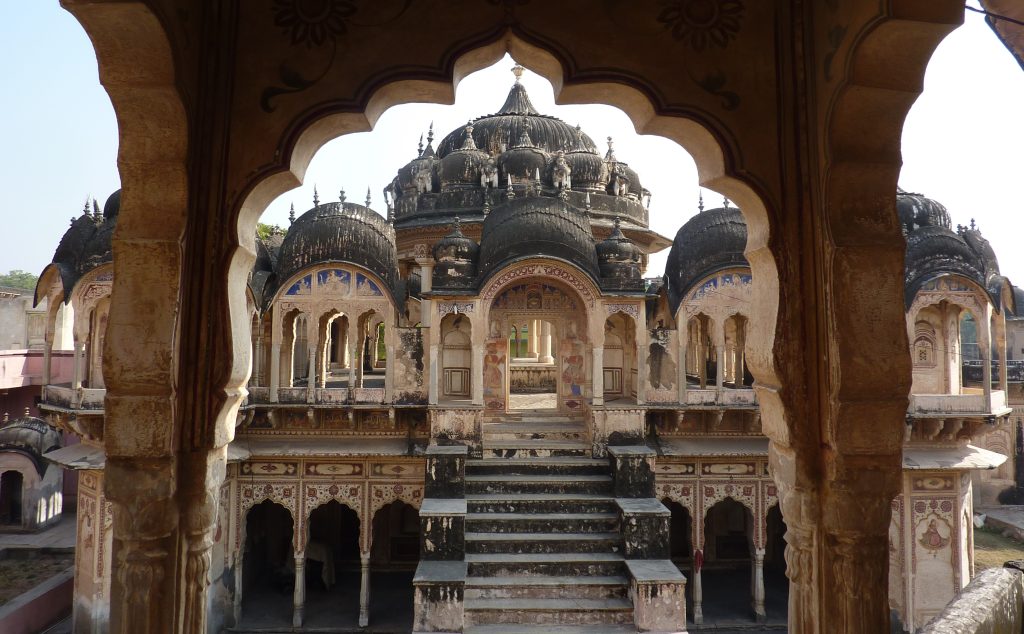

ostentatiously decorated havelis (see below). Many have survived and now collectively comprise one of the richest artistic and architectural

legacies in all India, if not the world: an incredible concentration of mansions, palaces and cenotaphs plastered inside and out with elaborate and colorful murals, executed between the 1770s and the 1930s. Considering the wealth of traditional art here, and the region's proximity to Jaipur, Shekhawati feels surprisingly far off the tourist trail – English is rarely heard, accommodation is thin, and there's little prospect of enjoyıng Western food. Precisely for these reasons it ranks among the most rewarding parts ot Rajasthan to explore, and of the few independent travelers who find their way up here, most invariably stay longer than planned, using Nawalgarh as a base for day-trips or leisurely walks into the desert. Shekhawati is crossed by a mainline railway, linking the major towns with Delhi, Jaipur and Bikaner. Travelling in Shekhawati is far more convenient by bus than rail. Fairly regular local buses, usually stop on the outskirts of town, though rarely operate after dark; Jeeps & taxis run according to demand. For less congested and precarious transport, you can rent a Jeep or taxi, starting at around Rs 3000 a day.

The Havelis of Shekhawati

The magnificent houses built by the rich merchants of Shekhawati were called havelis after the Persian word for "enclosed space". Each house would be entered from the street through huge arched porches with carved brass or wooden doors. Inside, you come into the forecourt, where visitors were received. Beyond, through the most ornate doorway of the house, is the main courtyard, where the women of the family could live in purdah, shielded from the eyes of the street. The forecourt is flanked by large pillared reception areas called baithak, each surmounted by a gallery where the women could sit if they wanted, privy to the business conducted below.

The most extravagant Marwari mansions might have four large courtyards, but three is more typical. The tradition of woodcarving that produced the imposing doors and window shutters is still strong, particularly in Churu.

The meticulous interior murals were painted by craftsmen from outside the region, using a vast array of intense hues, often highlighted with gold or silver leaf and mirrored designs. Like the early Catholic

churches in Europe, religious themes, especially episodes from the life of Krishna, were often depicted along the lintels above the main doors to cultivate faith among the uneducated masses. The outer walls were usually decorated by the masons who built the haveli, employing bolder designs and weather-hardy green, maroon and yellow ochres, with the occasional flash of blue. However, what set the Shekhawati murals aside from virtually all others in India are the seemingly incongruous, naive depictions of machines, events and contemporary fashions they invariably include, from scenes of British Redcoats marching into battle against the Moghuls to eccentric Victorian flying devices, steam trains and Edwardian memsahibs in big hats. When painted, these were all features of a faraway world that the women and poor townsfolk of Shekhawati had never seen with their own eyes. The wealthy men of the region wanted to share with their compatriots the extraordinary phenomena encountered on their travels trading in the great cities of the Rajasthan & Commissioned artists to paint these images, even though the artists had probably never seen the newfangled European novelties they were asked to depict.

Nowadays, most of the murals are faded, defaced, covered with posters or even just whitewashed over. In some ways this simply adds to their melancholy, haunting appeal, and there are so many – and the towns are so small – that you cannot fail to see a work of art virtually everywhere you look.

History

The first people to settle the lands north of Jaipur, the Musims of the Khaimkani clan, established two small states based at Jhunjhunu and Fatehpur in 1450. Their hold on the region was broken in 1730, when the Rajput Sardul Singh of the Shekhawat clan took over Jhunjhunu. Two years later he consolidated Shekhawati rule by helping his brother (already ruler of Sikar) to seize Fatehpur from its Muslim Nawab.

The local Marwari merchants were rivals in influence to the Rajputs, and it was this that led the Shekhawats to turn a blind eye to, and even sponsor, brigandry against them. In response, the merchants formed an alliance with the British (ever eager to get a foothold in the region), and in 1835 a small force of cavalry called the Shekhawati Brigade was set up under the command of Henry Forster and based in Jhunjhunu to control the brigands. This gave the Marwari the security they needed to build their magnificent havelis, and though many of them moved, encouraged by the British, to Bombay, Madras and especially Calcutta, they continued to send their profits back to Shekhawati, erecting elaborate buildings either to prove their worth as prospective bridegrooms, or simply as aid projects during times of famine. When the British left India, a number of Marwaris bought British industries and such names as Birla and Poddar remain prominent in business today. Although many merchant families have relocated to major urban centres, allowing their former haunts to fall into a state of disrepair, renewed tourist interest in the regions heritage has encouraged many of late to embark on restoration work.